One of the many tasks I had at a previous job was to look up references for furniture. The one I hated the most? Trees. There are only so many trees you can look up before they all start to resemble how trees used to appear before I got my glasses. But alas, each asset needed its own reference, and the trees had to be thematic, stylish, and match the rest of the room. They couldn’t all be green, or straight-limbed, or bushy. They had to vary.

It was during my never-ending search for a specific tree that I stumbled on a picture I thought had slipped past my AI blockers (aka setting search results to only show images from before 2018).

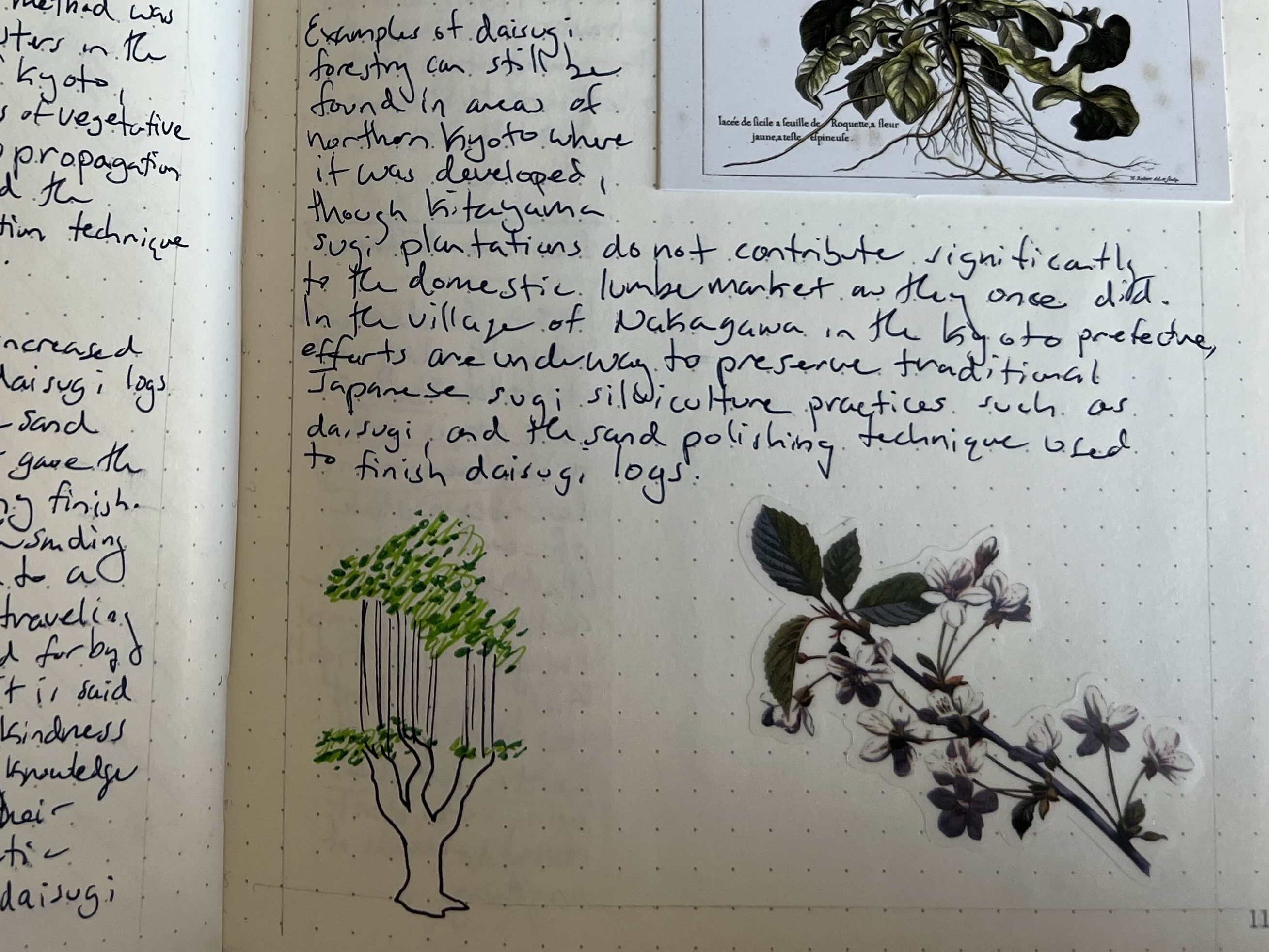

The trunks sloped gently up, ending in tightly clustered boughs that further split into branches with tufts of leaves pressed together like clouds. At a distance, the base shape reminds me of a wrist and hand artfully poised in that “limp reaching towards the heavens” way you see in paintings. If the tree ended there, it would be a normal tree—nice, good structure for a sketch, a little boring if color is involved.

Seemingly perched on top of the leaves were more trees. Unlike the tree beneath them, these trees didn’t bow. They were narrow and straight, with their branches contained at the top. They shared more similarities with the tall, high-branched trees in North Carolina than with the dense trees from which they grew.

Seeing this, I did the next logical thing. I spent the next hour researching Daisugi (litearlly “platform cedar”) instead of finding a picture of an inferior tree.

Daisugi is a sustainable forestry method that originated in the 14th century during the Muromachi period.1 Understandably, carpenters were picky about their wood and wanted lumber that was on the straight and narrow. Specifically, they wanted Kitayama cedar (if you want to know more about Japanese carpentry, let me know because I went on a research dive into that too — or you could check out this website).2 They also needed a lot of it, which caused a problem because land is a finite resource and trees take a while to grow. So, the carpenters went to the foresters and, after putting their heads together, came up with a plan that involved them getting really good at pruning trees.3

The process goes something like this:

- Find a nice, grown-up Kitayama cedar tree

- PRUNE PRUNE PRUNE (carefully. with calculation. this tricks the tree into growing new shoots. do it wrong you kill the tree.)

- Only the strongest survive. Prune the shoots that don’t meet standards.

- Wait 20-30 years

- Harvest

- Repeat steps 2-5 as needed4

Leave a comment